Many Massachusetts businesses today owe their survival in part to UI sustaining customers’ demand for products and services. Over the years, even though the UI system funding has run low, legislators have repeatedly waived rules requiring employers to increase their payroll contributions. The state has had to borrow from the federal UI Trust Fund which puts Massachusetts in debt to that fund. While no state UI system was prepared to handle the tidal wave of unemployment brought about by the pandemic, the Commonwealth is particularly badly prepared. In 2021, Massachusetts employers will be required to pay assessed interest on unpaid federal UI advances, and the state’s debt to the UI Trust Fund is anticipated to rise to about $5 billion.

Unemployment insurance achieves a variety of important economic and social benefits. Most obviously, it replaces income for individuals and families who, due to no fault of their own, are laid off or otherwise separated from paying work. Federal and state UI payments put money in people’s pockets and help boost consumer spending at precisely the time the economy needs that boost. UI can also improve productivity as it enables workers to take the time to search for employment that matches their skills. Because job losses have disproportionally hit Black and Latinx workers, the UI system has been particularly important for supporting families in communities of color.

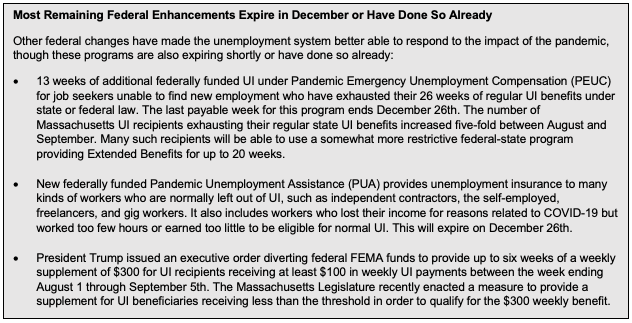

UI has been working as intended and federally funded enhancements to UI have been crucial in boosting its effectiveness. However, federally funded enhancements to unemployment benefits and eligibility have expired or will expire by the end of December.

There are many steps the federal government and the Commonwealth can take to strengthen UI and ensure it will better protect Massachusetts during this recession and in the future.

Unemployment Insurance Helped Save the Massachusetts Economy

Massachusetts suffered a tidal wave of job loss as a result of the pandemic. Employment fell by 23.5 percent, a drop of 874,400 workers between February and April 2020. This decline is more than the entire current labor force of eight Massachusetts counties combined. Massachusetts’ unemployment was higher than any other state in the nation in June and July, reaching 17.7 percent, a rate unprecedented since the Great Depression.

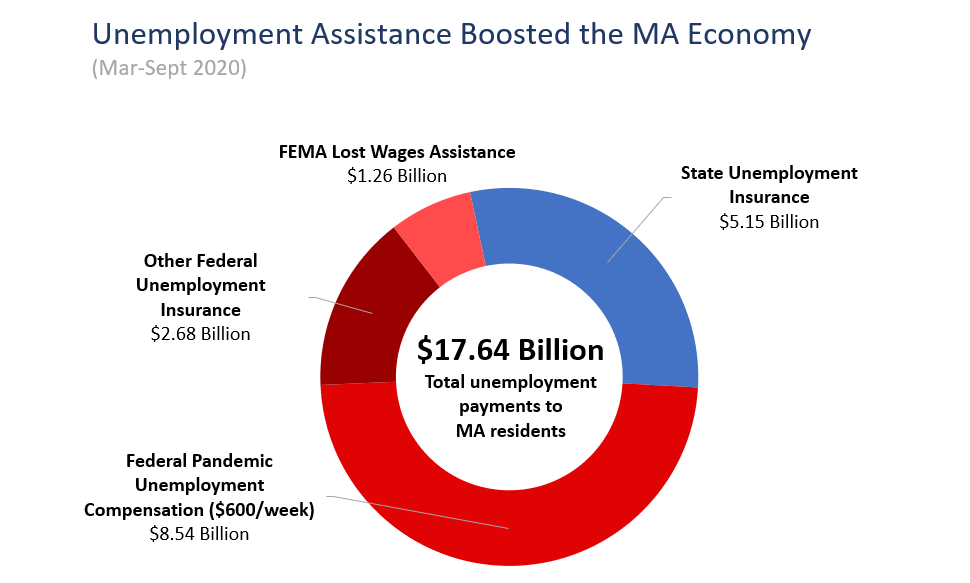

A total of $17.64 billion in unemployment payments were received by Massachusetts residents between March and September. Of this total, $12.48 billion were federally funded. Since UI benefits are taxable income, this could represent as much as $880 million in state income tax revenue.

Unemployment assistance is particularly effective at stimulating the economy during a downturn because it replaces lost income and is likely to get spent. By contrast, the $1,200 checks sent by the I.R.S. to most tax filers early in the pandemic were mostly stashed away or used to pay off past debts, especially by upper-income recipients.

Moreover, during an economic downturn the federal government typically covers half the cost of additional weeks of (“extended”) UI benefits and fully covers benefits during the current emergency. This injects much needed federal dollars into the state economy. Federal improvements to UI enacted early in the Spring have also provided tremendous support. The best-known federal enhancement to UI was an addition of $600 per week of Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (PUC), fully paid by the federal government. This benefit expired at the end of July after having injected an average of $2.14 billion a month into the Massachusetts economy since April. Indicators of poverty around the nation increased when these $600 UI benefits expired. In Massachusetts, applications for both federal food assistance (SNAP) and low-income cash benefits (TAFDC) increased dramatically in the weeks after the extra $600 in unemployment assistance expired at the end of July.

Unemployment Insurance Protected People of Color and Lower-Income Workers

Unemployment assistance has generally delivered support to workers who have most needed it, at least for workers in established full-time jobs. During the pandemic, UI has supported individuals and communities of color as well as lower-income workers, who have been hit hardest by the coronavirus and its economic harm.

Cities and towns with large populations of color have been hit particularly hard by job loss. Even when unemployment fell below ten percent (9.5 percent) statewide in September, the rates remained far higher in Lawrence (20.2 percent), Springfield (16.2 percent), Revere (16.1 percent), Brockton (15.1 percent), Lynn (14.4 percent), Holyoke (14.2 percent), Chelsea (14.2 percent), and Randolph (14.1 percent).

Race-based data is not available on recipients of new federal benefits for workers traditionally ineligible for UI, but for traditional state benefits, it is clear that UI benefits have been particularly important for Black and Latinx workers who are more likely to work in jobs that were hit with layoffs and furloughs in this recession. From March through the end of September 2020:

- UI recipients were 16.1 percent Latinx, compared to 10.8 percent of the workforce.

- At least 10.7 percent of UI recipients identified as Black, compared to 8.7 percent of the workforce.

The replacement of lost income for Black and Latinx households is particularly important to achieving equity as data show far lower levels of accumulated wealth for these families to fall back on. Examining the Greater Boston area, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston reports that, “overall, a typical black household earns roughly 60 percent of the typical white household but has only 5-10 percent of its wealth.”

Lower-wage workers have been hit harder by job loss during the pandemic and claimants of state UI benefits have likewise tended to be the more economically vulnerable, lower-income workers. The average unemployment claimant in July 2020 had lost a wage of just $734 per week, as opposed to the $1,039 weekly wage of unemployment claimants a year earlier, which is close to the state’s median wage.

Even so, UI does not reach all workers in need. Immigrant workers who may not have been officially authorized to work both during their previous employment and when applying for benefits cannot access unemployment assistance. Operational and bureaucratic inefficiencies during the pandemic have made it particularly hard for newly-authorized workers to submit documents and have them processed in a timely manner. A report by the New York based Fiscal Policy Institute also shows that more than $366 million in unemployment insurance contributions have been paid on behalf of approximately 113,000 undocumented workers in Massachusetts over the past decade, but these workers remain unable to collect a penny of benefits through either the traditional UI system or the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program.

Years of Shortchanging MA’s UI Trust Fund Will Leave It Deep in Debt

Each state places the UI payroll contributions collected from employers in a state trust fund. The system is designed so that during times of normal economic growth, states are expected to contribute sufficiently to their state funds during good times and build up these trust funds, and then draw from them during economic downturns – when they have the greatest need of UI and the least ability to fund relief on their own. States can borrow from a federal fund if their state fund runs low during times of high unemployment. They are expected to finance their own UI trust account with sufficient funds to pay a prescribed amount of benefit costs based on past recessions.

The problem is that Massachusetts has failed to comply with these federal expectations and state policymakers have repeatedly deactivated state laws meant to keep the UI Trust Fund adequately funded. Almost every year for over two decades the Legislature has blocked automatic increases to payroll contributions. In 2014, for instance, large business groups called to freeze the increases because it was the same time as a proposed increase to the minimum wage. In 2017, a two-year freeze on UI tax increases was offered to offset a now-expired fee on businesses to help pay for costs these businesses impose on MassHealth (Medicaid). Each time, blocking the automatic UI contribution adjustment increases the amount the Trust Fund is underfunded, and increases the potential need for future increases needed to fill the gap and comply with funding rules.

To help states comply with federal expectations for building their trust funds, the federal government gave them five years to phase-in compliance incrementally, but Massachusetts did not come close to achieving the required progress in any of those years. Last year, Massachusetts’ UI trust fund balance, which stood at $1.1 billion, would have needed to reach $3.9 billion to meet expectations.

Federal law requires states like Massachusetts, that have failed to adequately fund their own state UI system, to pay interest beginning in 2021 on outstanding federal UI advances. If the Legislature continues to block automatic increases to UI payroll contributions, then Massachusetts businesses will continue to pay interest payments on the growing balance of federal advances.

In the state’s October report, the UI Trust Fund is forecast to have a negative balance of $2.4 billion by the end of this calendar year. The state borrowed $1.76 billion from the federal UI account from June through September and was expected to continue borrowing to make payments through the rest of the year.

Due to the insufficient trust fund balance, existing Massachusetts law would automatically require private employers to steeply increase their payroll contributions from an average of $544 per employee in 2020 to $866 in 2021. The state calculates this increase would yield an increase of $940 million in contributions over the approximately $1.5 billion currently anticipated for 2020. Due to high levels of unemployment, the state UI Trust Fund balance is expected to be negative $4.8 billion at the end of 2021 even with these increased contributions.

If the Legislature had not blocked automatic payroll contribution adjustments, and had ensured that the state Trust Fund complied with federal rules, our UI system still would not have been fully prepared for the unprecedented tsunami of unemployment claims in the early months of the pandemic. But following the automatic safeguards would have averted deep debt, interest payments, and steep one-year increases in payroll contributions that will soon be required to avoid insolvency.

Many Federal and State Ways to Strengthen Unemployment Insurance

This year has underscored how crucial it is for Massachusetts to have a strong unemployment insurance system. It enhances our economic and social resiliency. It protects against human suffering when people lose their jobs through no fault of their own. Much can be done at the state and federal level to make our unemployment insurance system more robust and effective.

At the federal level, the main thing Congress should do is restore and continue the unemployment enhancements and supports that it created in March for what was expected to be a short-term crisis. The programs should be renewed until after the economic crisis has subsided. Federal UI should be extended to undocumented workers, especially those for whom contributions have been made to the UI system. To help state government’s finances, some state debt and interest payments to the federal UI trust fund should be forgiven if steps to increase future payroll contributions are implemented.

Massachusetts should adhere to federal expectations to sufficiently fund its UI system. It should pursue additional ways to make UI more financially stable, inclusive, and efficient by:

- Increasing the taxable wage base and indexing it to pay increases. The Massachusetts UI system levies payroll taxes only on the first $15,000 of an employee’s income. Over time, workers’ earnings increase, and payroll contributions should increase proportional to earnings to fund potential future UI benefits. As UI is still expected to replace lost income, there will be constant pressure to raise the tax rate on the same small tax base unless the base grows over time. A low taxable base amount also means that contributions on lower-income workers indirectly subsidize the UI benefits of higher-income workers and industries. This means that restaurants and other small businesses that have been severely impacted by the recession are inequitably responsible for a larger share of unemployment taxes. By contrast, Washington state’s taxable wage base is $52,700 and four other states set theirs above $40,000. Massachusetts should raise the base amount and index it, as 16 other states do. The taxable wage base could be set at the average wage or to a particular percent of that growing amount.

- Increasing outreach, access, and public awareness of UI. Only about half of unemployed workers in Massachusetts typically receive unemployment benefits although this rate is relatively high compared to other states. The Commonwealth should dedicate resources to publicize the program, ensure that employers inform workers who depart from jobs about how to apply for benefits, prompt telephone assistance for people having trouble applying online, provide information in multiple languages, and make the application rate of the newly-unemployed a publicized performance standard. This outreach is even more critical in an economic downturn when additional federally funded benefits are available.

- Stopping the misclassification of workers. The federal PUA benefits that expire at the end of the year and provide benefits to normally ineligible workers, have demonstrated the need to bring more workers into the UI system. Too many employers misclassify their regular workers as independent contractors or gig workers, or don’t legally recognize them at all. Massachusetts can strengthen rules to ensure businesses properly classify workers as employees. Massachusetts laws can also grant the Attorney General greater powers to enforce these laws.

- Improving collection of data by race. The fact that 16 percent of UI recipients’ race is unknown is a serious obstacle to identifying and addressing disparate racial impacts.

- Increasing use of “WorkShare” as an alternative to layoffs. “WorkShare” provides federally-supported relief where job losses take the form of partially reduced hours among multiple employees. It enables employers to remain connected to experienced workers who they can bring back on full time when business recovers. It allows workers to keep their jobs, as well as their medical and retirement benefits. It also takes advantage of favorable state reimbursement policies so that the Commonwealth receives greater federal funding. Studies show the employers tend to be highly satisfied with the program but few use it because they often do not know about it and the process to set it up can seem daunting. In Massachusetts, only 1.5 percent of all UI weeks were compensated through WorkShare arrangements at the end of September. This is one tenth the rate in Rhode Island. The state should redouble efforts to promote the program and make it easy to use.

- Modernizing the Unemployment Insurance IT system. Serious problems with the UI application and processing system have slowed and denied many benefits, especially during the early months of the pandemic. Numerous glitches continue to cause delays and erroneous denials. Websites can be optimized for mobile users so applicants can upload documents from their phone and greater access should be accorded to limited English proficient claimants, individuals unfamiliar with technology, and individuals with disabilities. The recent IT bond Act, passed as an emergency bill in August, authorized funds to plan, purchase, and implement an updated unemployment IT system. The Administration should convene and engage the advisory panel created by this act and heed the input of stakeholders, and then promptly appropriate the funds to make the system more accessible and user-friendly.

- Eliminating features that have a disparate negative effect on low-wage workers. Several formulas embedded in the UI benefit system deny access to workers who earn low wages, including reducing the duration of benefits and penalizing workers whose wages fluctuate through no fault of their own. The Legislature’s recent elimination of the 50 percent cap of total benefits when computing the $25-per-dependent additional allowance, which will begin 18 months after the Governor’s state of emergency ends, was a good first step in this direction. The allowance could also be updated for inflation.