Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data show that Massachusetts has a lower rate of outmigration of high-income households than of other households. U.S. Census data, meanwhile, show that Massachusetts is not seeing a significant drop in population. As a consequence, delivering large tax cuts to the state’s highest-income and wealthiest households to stem a non-existent exodus is misguided. Moreover, the best research shows that state tax levels have little impact on the decisions of high-income households about where to live. At the same time, tax cuts aimed at these few households would sacrifice revenue needed for public investments that address the challenges working families in Massachusetts face. These include the high cost of housing, childcare, and post-secondary education, as well as unreliable transportation systems.

The most recent IRS migration data (from 2020-2021) show that the rate of outmigration for households with incomes of $200,000 and above (the top income group shown in the IRS data) was lower than the outmigration rate for households with incomes below $200,000. While the difference in rates was not large (3.1 percent vs. 3.5 percent), it suggests that tax cuts that would sacrific large amounts of public revenue for to cut taxes primarily for the highest-income taxpayers is poorly targeted policy for addressing outmigration. These data are for a period in which migration decisions for many were influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly for higher-income households, which disproportionately had the resources and remote work options that allowed them to leave densely populated, COVID hotspots (like the greater Boston metro region) for second homes or rentals in rural areas. Future IRS and Census data will help us understand the degree to which moves made during the pandemic were a temporary or one-time response to a highly unsusual event or part of a longer-term trend.

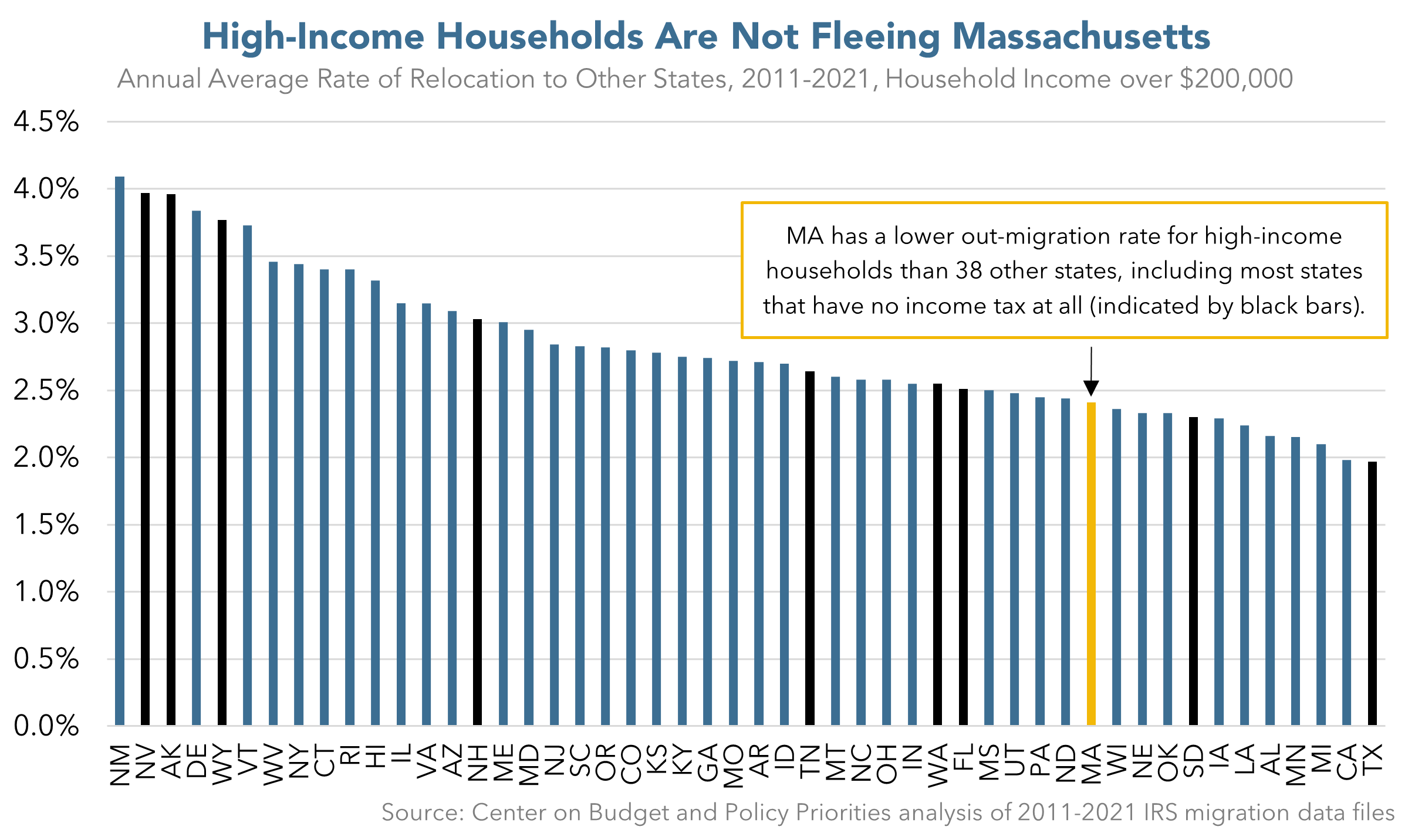

A look at the most current ten years of available IRS data suggests Massachusetts is not facing an acute or persistent problem with outmigration of high-income households. A forthcoming review of IRS data from 2011-2021 by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows that Massachusetts had a signficantly lower average annual rate of outmigration of high-income households (2.4 percent) during this 10-year period than of other households (3.1 percent). High-income households have not been fleeing the state.1

This same analysis shows that Massachusetts compares well to other states. Massachusetts had a lower average annual rate than all but 11 other states. (Presenting outmigration data as rates – rather than simply by the total numbers of movers – allows a proper comparison among states, regardless of differences in the states’ overall population sizes. It makes sense to look directly at outmigration separate from inmigration because there can be different issues driving these decisions, in addition to examining net migration flows, which we also do below.)

The data likewise debunk the notion that migration is motivated by differences in tax rates. Massachusetts had a lower high-income outmigration rate than seven of the nine states that have no income tax at all (see chart, above), including both Florida and New Hampshire. This is not a surprising result. The best empirical studies of how high-income households respond to state tax rates arrive at a similar conclusion: for the overwhelming majority of high-income households, decisions on where to live are not determined by state tax levels. The authors of the gold-standard study on high-income relocation, for example, summarize their findings by saying tax-induced relocation occurs “only at the margins of statistical and socioeconomic significance.” Only a very few high-income households move to avoid higher state taxes.

Thus, tax cuts for the rich would be a costly and ineffective “solution” to a problem Massachusetts does not have. To the extent that Massachusetts faces challenges with population growth, the solutions lie in addressing the struggles of low- and middle-income households, both those currently living in Massachusetts and those that would like to move here.

Other data similarly indicate Massachusetts is not facing a population crisis. In terms of overall net population change – from all causes and including people of all incomes – the most current estimates available from the U.S. Census Bureau show that Massachusetts’ population fell by just under 48,000 between April 2020 and July 2022.2 This is a decline of just under seven-tenths of one percent out of a total population of some seven million people. Eighty-five percent of this decline occurred in the fifteen months from April 2020 to July 2021, a period when the onset of the COVID pandemic was affecting death rates and (often-temporary) decisions about where to live during the pandemic. By contrast, in the subsequent period from July 2021 to July 2022, Massachusetts saw its net population decline by just 7,700 or one-tenth of one percent. (Interestingly, analysis of this Census data, performed and reported on by the New York Times, shows that the Boston Metro Area saw a net gain of some 8,000 remote workers during this same period. This finding raises doubts about claims that Massachusetts necessarily will suffer large worker losses with the rise of remote work options.)

There always will be some degree of outmigration. People often retire to warmer climates or to the mountains, or move to be near family or for a new career opportunity. In order to achieve a stable or growing population, however, Massachusetts can address the challenges that push people to leave when they otherwise would choose to stay, as well as problems that discourage people in other states and other countries from moving to Massachusetts. An important factor for many families in deciding where to live is affordability – especially for major expenses like housing, childcare, and education. Addressing these challenges will require sustained public investment in things like affordable housing, commuter rail service to new housing markets, affordable high-quality child care, and ready-access to debt-free higher education. Large tax cuts for a few, very high-income and wealthy households will impede the Commonwealth’s ability to make these and other investments in our people and our overall competitiveness. By contrast, targeted and well-funded state investments will help retain and attract the many people who want to make Massachusetts the place where they learn and work, start and grow a business, raise a family and eventually retire.

Endnotes

1 Forthcoming Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Gross Migration files, 2011-2012 through 2020-2021. High-income households in this analysis are those with federal Adjusted Gross Income of $200,000 or more. This is the highest income grouping provided in the IRS data. Due to a significant change in the IRS’ methodology, data prior to 2011 are not comparable with data from 2011 and more recent years.

The outmigration rate is equal to the number of high-income “outflow returns” (i.e., tax returns that were listed in the state at the beginning of the year but that departed from the state at some point during the year) divided by the total number of high-income tax returns present in the state at the beginning of the year.

2 These net population loss figures are the result of larger flows of people in and out of Massachusetts (as well as births and deaths among Massachusetts residents), the details of which are tracked in the Census data. These flows include the “net domestic outmigration” of some 111,000 Massachusetts residents between April 2020 and July 2022, as well as “net international in-migration” of some 61,000 new residents from overseas.