A variety of factors influence the decisions businesses make about whether to expand and where to locate their new or expanding operations. These factors include the quality of a state’s infrastructure; the skills of its workforce; the proximity to materials and customers; and the overall quality of life available to employees.1 A particular state’s tax policy – including tax rates, rules for calculating taxable income, and the availability of tax breaks – also plays a role, though not a primary one.2 This is not surprising given that state and local taxes account for as little as two percent of total business costs for the average corporation operating in the U.S.3

Nevertheless, if one wishes to compare relative levels of business taxation among the 50 states, it makes most sense to look at all state and local taxes paid by businesses, rather than focus on one type of tax (e.g., corporate income taxes or property taxes) or the taxes levied only at one level of government (e.g., county or state level taxes). Some states collect more revenue from businesses using property taxes (typically, a local tax), while other states rely more heavily on corporate income taxes, gross receipts and excise taxes, or general sales taxes (typically, state-level taxes). A meaningful, apples-to-apples comparison of total business tax levels in different states must account for all the ways that state and local governments collect taxes from businesses.

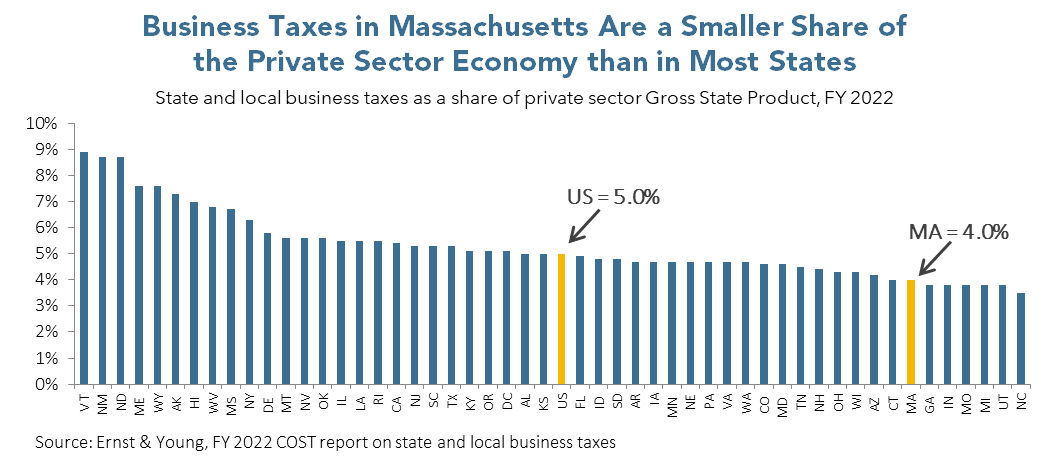

The Council on State Taxation (COST) – a Washington DC based trade association representing over 500 multistate and multinational corporations – produces an annual report that examines the full set of state and local taxes paid by businesses in each of the 50 states. Their most recent report (released in December 2023) shows Massachusetts having among the lowest “total effective business tax rates” of all states. This is a measure of total, combined state and local taxes paid by businesses, as a share of private sector output (i.e., Gross State Product).4 According to COST, in Fiscal Year 2022 (FY 2022), only six other states had a lower total rate than Massachusetts.5

In other words, in all but a handful of other states, businesses pay more in total state and local taxes relative to the value of their economic activity than they do in Massachusetts. Notably, many states that tout themselves as having low taxes for business actually have higher total effective business tax rates than Massachusetts, including New Hampshire, Florida, and Texas. Had Massachusetts’s total effective business tax rate (4.0 percent) instead been equal to the U.S. average (5.0 percent), Massachusetts businesses would have contributed an additional $6.0 billion in state and local taxes in Massachusetts in FY 2022.6

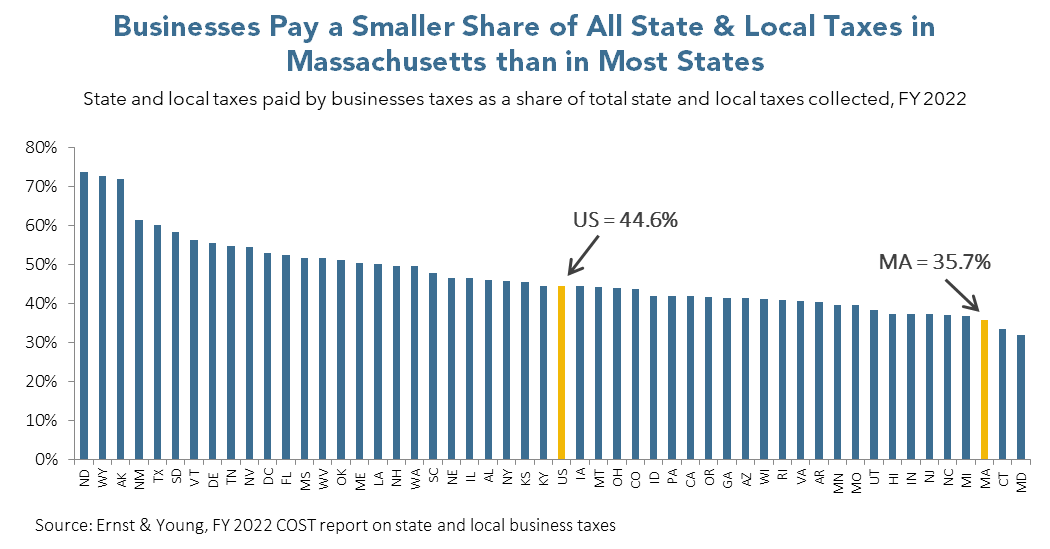

In their study, COST also reports the share of all state and local taxes that is paid by businesses in each state. A smaller share of taxes paid by businesses means a larger share must be paid by other groups, such as consumers, residents, landowners, and workers.7 The report concludes that Massachusetts businesses together paid 35.7 percent of all state and local taxes collected in the Commonwealth in FY 2022. This percentage is far below the U.S. average of 44.6 percent. In only two other states (Connecticut and Maryland) did businesses provide a smaller share of total state and local taxes.8

Improving Revenue Adequacy and Corporate Tax Fairness in Massachusetts

By important measures – like those shown in the COST study – Massachusetts has low overall business tax levels compared to other states. As such, Massachusetts is well-positioned to raise taxes on businesses while remaining at or below the U.S. average. In particular, raising taxes on business profits (as opposed to taxes on business property, for example) means that the businesses generating the largest profits are the ones contributing the most to support the many government functions on which all businesses depend. There are many options for raising state-level taxes on business profits, including:

- Raise the tax rate applied to corporate profits. (Notably, like many states, Massachusetts has seen a significant decline over the last four decades in the share of state tax revenue generated through its corporate income tax – even as corporations have claimed a growing share of national income.)

- Eliminate expensive and wasteful business tax breaks such as the film tax credit.

- Close the “water’s edge loophole” that allows profitable multinational corporations to avoid state taxes by shifting profits onto the books of subsidiaries located in offshore tax havens. The water’s edge loophole can be closed by adopting “worldwide combined reporting” (WWCR). WWCR would help level the playing field for most smaller Massachusetts businesses, which typically do not have overseas subsidiaries. It would enable them to compete more effectively against large multinationals that often engage in elaborate tax avoidance schemes.

Though by no means an exhaustive list of the possibilities, taken together, these tax reforms would raise hundreds of millions of dollars in additional state revenue annually. Importantly, Massachusetts recently altered its tax laws in a way that eliminates a potential downside to raising taxes on corporate profits. With the switch to “single sales factor apportionment” (SSF),9 the share of a corporation’s nationwide profit that is taxable by the Commonwealth now depends only on the value of sales the corporation makes to Massachusetts customers relative to its nationwide sales. Thus, with SSF in place, businesses do not have any incentive to reduce their operations in Massachusetts as a way to reduce their income taxes. Downsizing their workforce and/or capital investments in Massachusetts no longer affects the income tax a corporation owes to the Commonwealth. Under SSF, the only way to reduce the share of profits that is taxable by the Commonwealth is for a business to reduce the share of sales it makes to Massachusetts customers. Since sales are the basis for corporate profits, actively reducing sales is not a tax reduction strategy any business will pursue.

Conclusion

Public investments play a critical role in supporting business activities. As such, businesses have an obligation to help pay for these investments. Massachusetts has significantly lower overall business tax levels than do most states. Raising business taxes – particularly on large, profitable corporations – is an appropriate and practical way for the Commonwealth to maintain and enhance its investments in education, transportation, healthcare, housing, public safety, the environment and more.

Endnotes

1 Iowa Policy Project, Peter Fisher, Grading the States (see third paragraph on landing page): http://www.gradingstates.org/the-problem-with-tax-cutting-as-economic-policy/state-and-local-business-taxes-are-not-significant-determinants-of-growth/

2 Political Economy Research Institute, Thompson, Jeffrey, “Prioritizing Approaches to Economic Development in New England: Skills, Infrastructure, and Tax Incentives”,September 2010, pg. 10: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6248287.pdf

3 Using data from the most recent IRS Statistics of Income for corporations (2020), Table 2.1, nationwide, taxes and license fees together account for 1.9 percent of total business expenses. This matches the U.S. average during the years 2003-2016. See Iowa Policy Project, Peter Fisher, Grading the States (see second paragraph, accompanying pie chart, and endnote #2): http://www.gradingstates.org/the-problem-with-tax-cutting-as-economic-policy/state-and-local-business-taxes-are-not-significant-determinants-of-growth/. See also testimony to the New Hampshire Legislature from Robert Tannenwald, former Director of Research for the New England Public Policy Center, a research policy division within the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 11-4-2010: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3314

For additional detail on the IRS SOI and why it is the best source for data with which to calculate state and local business taxes as a share of total business expenses, see Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report, April 3, 2008, endnote 6 (pg. 8): https://www.cbpp.org/research/almost-all-large-iowa-manufacturers-are-already-subject-to-combined-reporting-in-other

4 Council on State Taxation (COST), “Total State and Local Business Taxes, FY2022,” December 2023. See pg. 14.

5 Council on State Taxation (COST), “Total State and Local Business Taxes, FY2022,” December 2023. See Table 5. on pg. 15. As in past years, the update to this study was conducted on behalf of COST by Ernst & Young. COST was founded originally through the Council of State Chambers of Commerce and remains associated with that organization.

6 Building off of the numbers presented in the COST report, the U.S. average TEBTR (5.0 percent) was 25 percent higher than Massachusetts’ TEBTR (4.0 percent). COST pegs total state and local taxes paid by businesses in Massachusetts in FY2022 at $24.1 billion. (See Table 5 on pg. 15) Twenty-five percent of this total equals $6.0 billion. ($24.1 billion x 0.25 = $6.0 billion.)

7 The methodology used in the COST study assumes that none of the cost of state and local business taxes is passed along to other economic actors. The general understanding among economists, however, is that tax costs in fact are borne by a combination of business owners/shareholders, workers, landowners, and consumers, with variation by industry and location. See for example, Serrato & Zidar, “Who Benefits from State Corporate Tax Cuts?”, American Economic Review 2016, 106(9): 2582-2624 https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20141702

8 Council on State Taxation (COST), “Total State and Local Business Taxes, FY2022,” December 2023. See Table 6.

9 According to the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, this change in our tax laws will cost the Commonwealth $85 million a year in lost revenue.