The Governor’s signing of the conference tax package in late September wrapped up a complicated, 20-month process. The package is the largest set of tax changes the Commonwealth has seen in some 15 years and will cost the Commonwealth over $1 billion each year in forgone tax collections. As MassBudget noted previously, the package includes some elements that improve tax fairness, and racial and economic equity (i.e., “progressive” elements), as well as other elements that make our state tax system less fair and thereby worsen economic and racial inequality (i.e., “regressive” elements).

Is the tax package regressive or progressive overall?

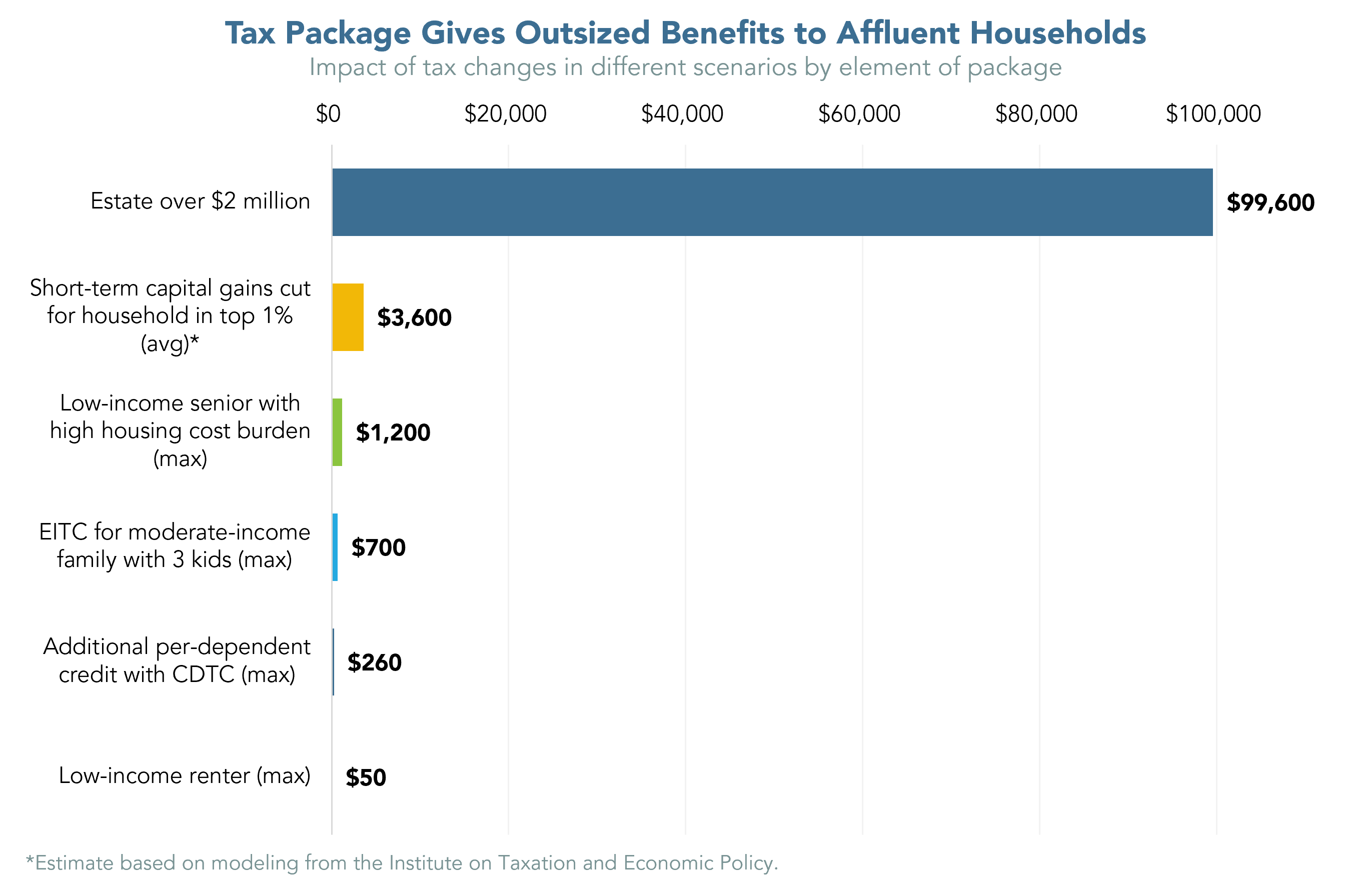

This is a hard question to answer conclusively. For some elements of the package, data is lacking on how benefits are distributed among income and racial groups. This makes it difficult to assess with precision the equity impacts of the package as a whole. Broadly speaking, however, the package delivers very large per-household benefits to the small number of high-income and wealthy households in Massachusetts, while delivering typically much smaller per-household benefits to the state’s many low- and middle-income households.

Some of the tax changes in the package have smaller costs in the first few years and then ramp up in cost in future years. This MassBudget analysis examines the longer-term impact of the package’s tax changes. To better capture this cost growth we use estimates for Fiscal Year 2027, the year furthest in the future shown in materials distributed by the Legislature.

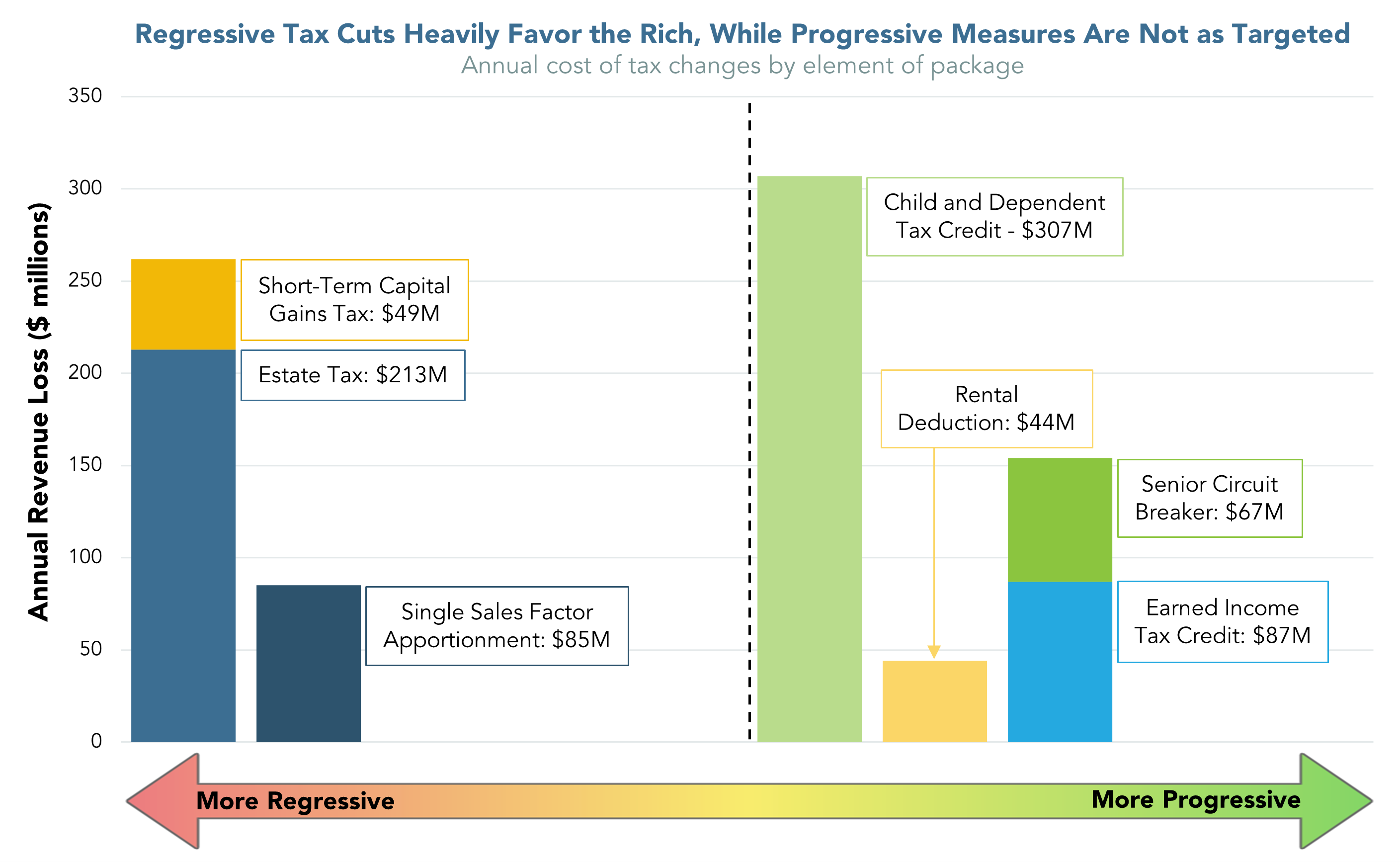

Roughly a third of the overall package’s net cost – some $347 million out of an estimated total package cost of about $1.018 billion per year in forgone revenue1 – consists of very regressive changes, ones that overwhelmingly will benefit the state’s relatively small number of very high-income and wealthy households.2 All of these regressive changes reduce taxes on money received as a result of ownership – whether through inherited wealth, assets sold for a profit, or income received as a result of ownership in a corporation. Ownership of wealth is highly concentrated among a relatively few, mostly white households. Because these tax cuts will deliver so much to so few, the per-household size of the tax cuts these households will receive is large, often amounting to many thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. Some very high-income and wealthy households will see cumulative tax cuts exceeding $100,000 in a single year. Because these households are disproportionately white, these elements of the tax package will worsen existing racial disparities in Massachusetts.

About half of the overall package’s cost – or some $505 million – results from progressive changes, ones that clearly will deliver a substantial share of their direct benefits to low- and middle-income households.3 These progressive tax changes, however, do not focus their benefits on the lowest-income households as narrowly as the regressive tax cuts in the package focus benefits on the most affluent households. Still, some of the progressive changes – like increasing the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Senior Circuit Breaker Tax Credit – deliver their benefits overwhelmingly to low-income households. Others — like the Child and Dependent Tax Credit and the Rental Deduction – clearly help low- and middle-income households, but also deliver a substantial share of their benefits to upper-middle income households (though little goes to the very highest income households). Additionally, the progressive tax cuts typically deliver much smaller per-household benefits than the regressive tax cuts do. Importantly, several of the progressive tax cuts will benefit BIPOC households disproportionately, thus pushing back against existing racial inequities in Massachusetts.

Approximately 15 percent of the overall package cost is due to elements that are not as easily assigned to the progressive or regressive buckets. These include various credits associated with construction of housing, commuter transit benefits, dairy and cider taxes, lead abatement credits and more.

Major Progressive Elements

Increasing the value of the state Earned Income Tax Credit is the most progressive change in the tax package. Providing a total tax reduction of $87 million a year, close to 400,000 low-income working households will benefit from this change. While the maximum credit amount will rise by about $700 per year, not all eligible households will receive the maximum credit. Almost 90 percent of the benefits will go to households with the lowest 40 percent of incomes.

Doubling the maximum credit available through the Senior Circuit Breaker program from $1,200 to $2,400 a year is another clear win for increasing equity, potentially helping over 100,000 households. Available to seniors with low- to moderate-incomes and high housing costs, the change will cost an estimated $67 million a year. While the maximum possible credit amount will rise by $1,200, not all eligible households will receive the maximum credit. Almost 80 percent of the benefits will go to households with the lowest 40 percent of incomes.

An increase in the cap on the Rental Deduction from $3,000 to $4,000 can provide an estimated 881,000 households with a small tax cut of up to $50 a year. This additional benefit is estimated to cost $44 million a year, with two-thirds of the benefits going to households in the bottom 60 percent of incomes.4 This change delivers only a small and not especially targeted benefit, though it reaches many households. Unfortunately, because this tax cut is structured as a deduction rather than a refundable credit, some of the state’s lowest income households will be unable to access some or all of its potential benefit.

Replacing existing, similar credits with the new and more generous Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDTC) is a step that will help an estimated 565,000 families per year. The CDTC will provide a credit of $440 per eligible dependent, up from the current $180 or $240 credit amounts provided by the existing two credits. Unfortunately, legislators chose not to index the credit to inflation, as had been proposed. As a result, the ability of the credit to help offset families’ dependent care costs will erode over time. With an estimated annual cost of $307 million per year, the CDTC is the single largest element in the package.5 The benefits are spread broadly among low-, middle-, and even upper-income households. Nevertheless, the credits will represent a larger portion of household income for low- and moderate-income recipients than for high-income households, thus making the CDTC progressive.6

Finally, there are two elements of the package that have important, economically progressive implications, and which do not add to the overall cost of the package. The first addresses the single filer loophole which otherwise could result in the loss of up to $600 million of revenue from the new millionaire’s tax.7 Secondly, lawmakers also improved our tax system by reforming the 62F tax cap provision. In the future, any refunds provided to taxpayers will be distributed equally to all filers. This is in contrast to the current structure, which delivered tens of thousands of dollars to very high-income households and single-digit refunds to the lowest-income filers. Nevertheless, the 62F tax cap law remains a deeply flawed policy that, in the future, may again arbitrarily reduce public investment. However, with the change included in the tax package, 62F will no longer worsen income disparities in the process.

Major Regressive Elements

The most costly of the major regressive elements included in the tax package is the $213 million per year cut in the state estate tax. Lawmakers have provided a credit of up to $99,600 against any estate taxes due. In effect, this new credit means that estates with taxable values of $2 million and less now will pay no estate tax in Massachusetts (Prior to the change, estates valued at under $1 million paid no estate tax). Estates valued above $2 million – even those with taxable values of tens or hundreds of millions of dollars – also will receive the $99,600 tax cut. Only several thousand estates – those of the very wealthiest households – are subject to the Massachusetts estate tax in any year. Thus, this tax cut will provide a very large benefit to a very small number of families and, given existing disparities in wealth by race, will worsen the large existing racial wealth gap.

In addition to cutting the estate tax, lawmakers also cut the tax rate applied to short-term capital gains, a form of income that goes almost exclusively to the state’s highest income households. Short-term capital gains are income from the sale of assets (like stocks, bonds, real estate, art, etc.) held for less than one year. The Department of Revenue estimates that the rate cut, from 12 percent down to 8.5 percent, will cost the Commonwealth some $50 million a year. The cost, however, may be far higher in years with especially strong stock market performance.8 Almost three-quarters of the benefits from this tax cut will go to the top 1 percent of households, while less than 3 percent of the benefits will go to the bottom 80 percent of households.9 Like the estate tax cut, the cut to short-term capital gains will worsen racial inequality in Massachusetts.

Finally, lawmakers adopted a different method for determining how corporations will calculate the amount of tax they owe to the Commonwealth on their profits. Referred to as “single sales factor apportionment”, this method is one already used by Massachusetts businesses in some industries. Notably, single sales factor apportionment has failed to deliver the benefits touted by its supporters. Adoption of this mandatory apportionment method will result in a loss of $85 million a year in state tax revenue. All of the benefits will go to profitable businesses, operating in Massachusetts, that make a substantial share of their sales to out-of-state buyers. Small shops, grocery stores, and other local businesses that sell only to customers in Massachusetts will see no benefit from this change. Instead, these small businesses will have a harder time competing against the typically larger, multi-state companies that will receive this new tax advantage. Like the rest of us, local businesses also will face the likelihood of reduced state investments in the basic infrastructure that allow businesses and communities to thrive.

Endnotes

1 Legislative documents put the total, annualized cost of the package at $1.018 billion for Fiscal Year 2027.

2 In this category are: Single Sales Factor ($85 million), Short-Term Capital Gains Cut ($49 million), and the Estate Tax Cut ($213 million), totaling $347 million.

3 In this category are: Child & Dependent Care Tax Credit ($307 million), Earned Income Tax Credit ($87 million), Senior Circuit Breaker ($67 million) and the Rental Deduction ($44 million), totalling $505 million.

4 Distributional analysis from Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy modeling

5 The CDTC will be fully implemented in Fiscal Year 2025, when the cost is estimated to be $301 million. For consistency’s sake, we present here the cost of the CDTC as estimated for Fiscal Year 2027.

6 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy modeling

7 Department of Revenue analysis of single filer loophole, “DOR comments on Section 24 of Senate Bill S.2406”, Footnote 1.

8 The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, for example, estimates that the annual revenue loss from this rate cut could exceed $160 million. Under this scenario, households in the top 1 percent would see average tax reductions of some $3,600 a year due to the rate cut.

9 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy modeling